Pain

Pain is a universal human experience, but it is also highly individual. It can be hard to evaluate the exact cause of pain, but it is always a signal that something potentially dangerous is happening to your body.

Pain is often considered to be a normal part of sports, aging, and childbirth. While it is true that pain is part and parcel of being human and that some pain is unavoidable, pain is not meant to be felt for longer periods of time.

Pain is, first and foremost, a signal that something intense, overwhelming, and most likely damaging is happening to your body. At the most basic level, the experience of pain tells you to stop what you are doing: stop lifting the heavy thing, remove your hand from the fire, take care of the wound.

Pain receptors or nociceptors are sensory neurons that are found throughout the human body: in the skin, some internal organs and even the bones—in the bone marrow and the bone tissue itself. Famously, there are no nociceptors in the human brain— headaches occur through other structures in your head such as the blood vessels, and the nerves and muscles in your neck and face.

The sensation of pain occurs when pain receptors respond to various damaging (or potentially damaging) stimuli by sending electrical signals to the spinal cord and the brain so that you can then react accordingly.

The stimuli that the pain receptors respond to can be both external and internal. In some cases, when encountering an external stimulus, your body will immediately engage in automatic and involuntary reflex actions to withdraw from the pain. When facing severe, damaging stimuli, we automatically change what we are doing.

Whenever we experience a strong, immediate feeling of pain, it is almost impossible not to change our behaviour and look for help. Pain is the number one reason why people look for medical assistance.

Types of pain

There are many ways to categorize pain: by localization (headaches, joint or muscle aches and so on – if it is in your body, it can most probably hurt) or, for example, by the cause of pain.

Nociceptive vs neuropathic pain

Nociceptive pain is pain caused by the direct irritation of the pain receptors. Real or perceived damage to the tissue around the pain receptors is usually visible. Neuropathic pain occurs when the neural pathways themselves are damaged. Damage to the nervous system can occur due various diseases such as cancer, diabetes, or multiple scleroses, or due to a genetic condition.

Phantom pain is also a type of neuropathic pain. This type of pain occurs in amputees when the patient reports feeling the sensation of pain in a limb that is no longer there.

Acute vs chronic pain

Acute pain is temporary and develops as a direct response to an intense stimulus such as an injury or physical trauma or an acute disease or infections. The pain felt in childbirth is also acute. Acute pain is an aspect of the body’s defence mechanism. Such pain disappears once the underlying condition has been treated, usually within about one month.

Chronic pain is pain that persists for several months or longer. It can be caused by an illness such as fibromyalgia, endometriosis, arthritis, migraine or cancer. Any untreated illness or injury can also cause chronic pain. Chronic pain is hard to treat and fully overcome, as very often the direct cause for the pain has already disappeared, leaving only the faulty “information” in your neural pathways.

Chronic pain may not be as strong as acute pain, but it can have highly negative effects both physically and psychologically due to its persistent nature.

Risk factors for chronic pain include:

- genetics—for example, if migraines run in your family, you have a higher risk of developing them

- being underweight or overweight

- old age

- having diabetes

- having a high-risk career or hobby—for example, if you put a lot of pressure on your joints by regularly lifting heavy objects or doing extreme sports

- previous injuries

- smoking

- having a sedentary lifestyle

- stress

Pain is different for everyone

The pain threshold—the moment at which the sensation of pain becomes too hard to bear—can be very different for different people.

The factors contributing to the pain threshold include gender, genetic factors, previous exposure to the stimuli, physical fitness, the health of your skin, and even such seemingly insignificant details as a person’s mood on a specific day.

Of course, pain is hard to miss when you are the one experiencing it. In others, pain is not always so noticeable, especially if it is chronic and the person has become used to managing it, or if the person cannot clearly express themselves. This lack of sensitivity to the experience of others has led to many unfair practices in the past.

Many members of the medical profession believed that babies do not feel pain up until the 1980s! This, of course, is not true. The thinking was that as the infant cries in response to all kinds of stimuli, painful or not, their nervous systems have not yet fully developed, and they must not truly recognise pain.

The fact that babies do feel pain has now been backed up by MRI scans. Research suggests that babies are even more sensitive to pain than adults. What mother needs a scientist to tell her that?

Unfortunately, if the person in pain cannot communicate their experience in a way that others can understand, they are often ignored and left to suffer. This can and does happen to people living with disabilities and chronic illness. In fact, it can happen to just about anyone.

It can be very difficult to evaluate pain and communicate the experience effectively. How does the pain feel? Is it a sharp pain? A pulling or throbbing sensation? Where is the pain located? The vocabulary we use to talk about pain is often insufficient.

To overcome the difficulties we have in communicating about pain, researchers have developed various questionnaires and ways of reporting our experiences. For example, your doctor might ask you to evaluate your pain on a scale from 1 to 10 where 0 means “no pain” and 10 means “the worst imaginable pain”. For the most part, doctors do not expect you to say anything close to 10 during an examination because a person experiencing such intense pain wouldn’t be able to speak at all.

Do not be afraid to carefully evaluate your pain and give a lower number. A healthy, well-functioning body should not be feeling any pain at all. And even a 1 or 2 out of 10 can be harmful, especially when the pain is chronic.

Pain and stereotypes

Women are often dismissed when reporting pain in their body, either because they are deemed too “sensitive” to properly evaluate the seriousness of the pain or because they are expected to just bear any and all pain related to the menstrual cycle, pregnancy, or just being a woman in general.

Similar stereotypes can be seen with other groups as well. For example, people with obesity are often not examined thoroughly enough in medical settings; unaware of their bias against the obese, doctors tend to ascribe all complaints to excessive body weight. While obesity is a contributing factor to many illnesses, and pressure on joints can result in pain, by refusing to investigate other possibilities real harm can be done if the person is suffering from other serious conditions that require treatment.

Good pain?

Culturally, our attitudes toward pain can be quite ambiguous. We sometimes believe that there is value in feeling pain if it is in pursuit of a worthy goal: the pain from cosmetic procedures, for example, or physical training.

The “no pain, no gain” attitude can be very damaging, in sports and in other areas of life. Some soreness and muscle pain after physical activity is normal. However, driving oneself to exhaustion can be dangerous.

In sports, just as in other areas, pain is a signal that something is wrong or about to cause injury. If pain is ignored, it can lead to serious health problems and burnout.

Pain as a part of sex is another subject entirely. For some people, managed pain provides an extra dose of excitement in bedroom. You can read more about sexual fantasies here. The bottom line is that experiments in the bedroom should always be consensual. And the sex act itself should not be painful.

Pain relief

Various pain relief medications (analgesics) are available, either over the counter at the drug store or with a prescription from your doctor.

Aspirin and ibuprofen are two of the most common over-the-counter pain relief medications. They reduce pain by blocking the chemicals released by the injured tissue. Ibuprofen also reduces swelling.

It may seem that these medications target the painful area specifically, but they actually travel throughout the blood stream, affecting all places where cells release specific pain hormones.

These medications can be used to address aching muscles and joints, painful periods, headaches, and other symptoms. Aspirin and ibuprofen are relatively safe, especially if used irregularly. However, they only treat symptoms and do not heal the real causes of pain.

Opioids such as morphine and fentanyl are stronger pain medications that are usually only available with a prescription. They are used to relieve severe pain resulting from serious injury, a chronic condition, or during post-surgery recovery. Sometimes these medications are given to cancer patients to relieve the pain of treatments.

Opioids are similar to endorphins—the neurotransmitters that your body naturally produces to reduce pain. If overused, they can become addictive. Opioids also have stronger side-effects than less severe pain medication.

People with chronic pain sometimes require additional antidepressants, as the pain does not have a physical source that can be treated.

Natural remedies

Often pain can be prevented or at least relieved using natural remedies such as:

- ice applied to swollen muscles

- a cold compress to relieve a headache

- a warm compress for arthritis

- yoga and stretching for muscle health and mobility

- breathing exercises to calm both mind and body

- ginger to reduce muscle pain, swelling, and other types of inflammation

- turmeric to reduce ulcers and relieve indigestion

- herbal tea for a variety of ailments

- acupuncture for a variety of ailments

- essential oils for a variety of ailments

- a warm bath to relax

Reducing stress—both external and internal—can have a significant impact on pain management.

Be careful when self-medicating and always consult a healthcare professional if the pain returns.

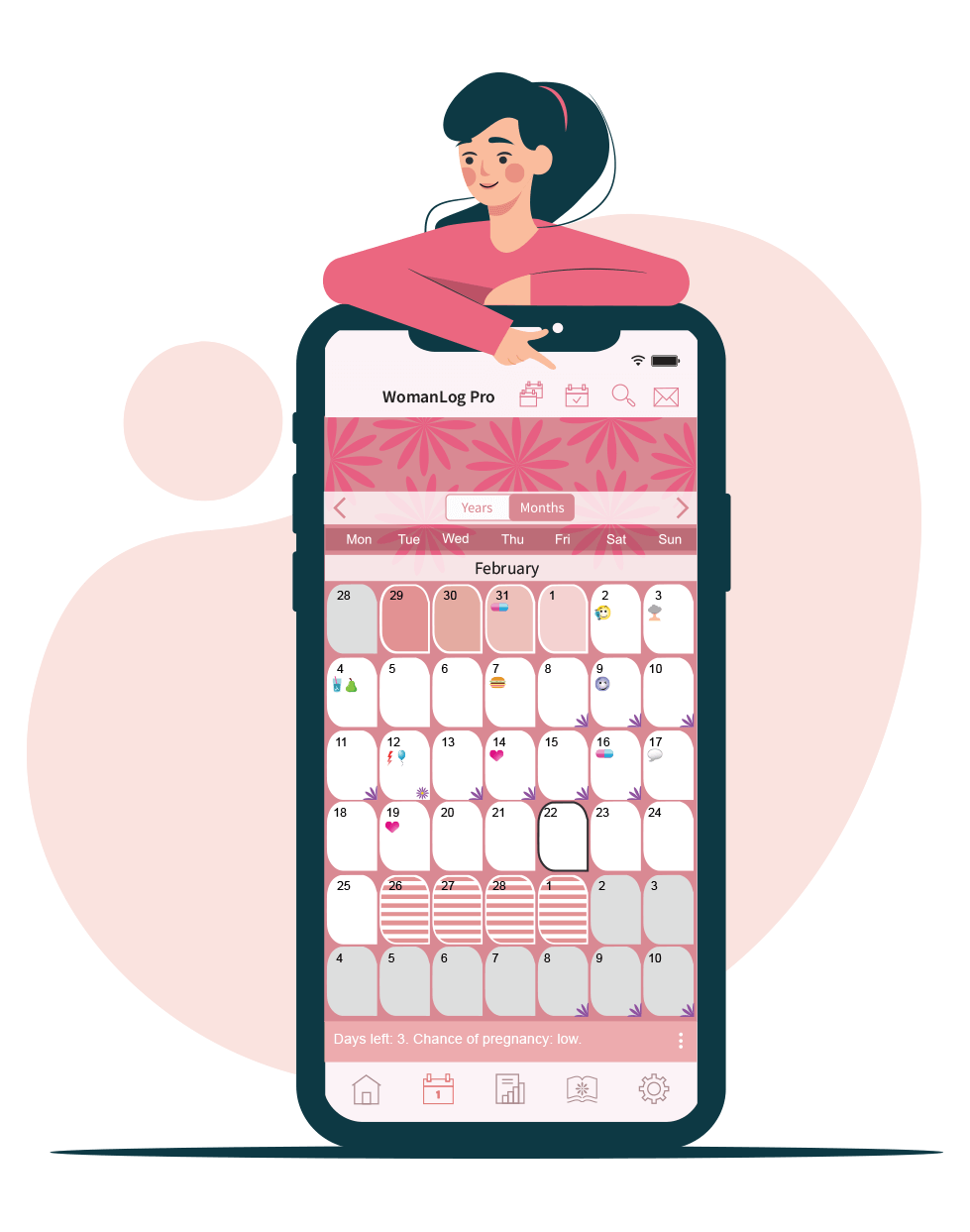

You can track your period using WomanLog. Download WomanLog now: